Harvey Johnston, front left, who gave the North Ronaldsay Harvest Home address, makes sure his poem on the history of the isle is quite up to date during supper. (Picture: Alasdair Henderson)

As I begin this letter, writing in the evening, the moon is not far from being full.

It shines a little hazily through high, almost gossamer thin, cloud, and in the east a few crofts are silhouetted against the moonlit sea.

There is a sort of constant hushing sound in the night air which, in the old Orkney dialect, would be described as the ‘swaa o’ the sea’.

In fact this whole day has been absolutely magnificent. It has been as warm as a summer’s day, with a light southerly wind and at times high, rippling, white clouds scattering across the pale blue of the early November sky.

This morning, when flying to Kirkwall in a Loganair plane, I was watching the changing colours of the landscape below. The different islands set against the blue sea, with white shifting surf here and there, looked quite beautiful in the early morning sunshine.

As we began to cross over Sanday I could see the little jetty that had been built at the ‘black rock’. In the old days that was the point on Sanday where the North Ronaldsay mail boat landed passengers and carried the Royal mail to and from the island.

In fact, when it was built, in the 60s, it was too late for the convenience of passengers; for, by then, Loganair was up and running, and shortly both mail and passengers would cross the sometimes turbulent North Ronaldsay Firth by aeroplane.

As we passed by, I could not help but reflect on the days when generations of travellers, to and from North Ronaldsay (when it was weather), slithered and slipped across that old seaweed-covered ‘black rock’.

Further across Sanday, at the south end, as we passed by, I could see the much larger jetty at Kettletoft – the main contact point for the North Isles boats before the days of ro-ro. It has now become almost a ghost jetty as the ro-ro ferries dock at the opposite end of the island.

Many a time, as young folk of school age in the 50s, travelling from Kirkwall, we would stop in past the Kettletoft Hotel for a pot o’ tea and a bite.

Most of us were on our way home for holidays to North Ronaldsay at either Christmas, Easter or summer. I suppose we were all a little excited and generally looking forward to getting home after months of being isolated in Kirkwall.

In the dining room of the hotel I particularly remember the wonderful brown cookies that were baked locally, and in my mind’s eye I can still see two fine watercolours that always took my fancy and which hung on the walls of the room.

Davie Sinclair, How, Sanday, tells me that they were painted by a Marjorie Begg. Her father was the Procurator Fiscal in Orkney for a time, I believe, before the last war.

The watercolours depicted scenes on the Orkney Mainland – not in Sanday as I always imagined. I wonder where those paintings are today?

Later, as we came in over the Grimsetter airport, more history could be seen for, here and there, a bomb shelter or some other small wartime building still remains in the vicinity.

During the Second World War, this aerodrome would have hummed with activity as fighter planes landed or took off, and men and women in uniform would have been busy with their various duties.

You know, it’s funny how things relate: for, while briefly visiting a shop in town, I heard a 40s recording playing, of Major Glen Miller’s band – probably that same war-time tune would have been very familiar at Grimsetter all those years ago.

And on this November day Kirkwall looked grand in the sunshine – even some wasps, bees and other insects were having a last fling, bamfoozled as they no doubt were with the late warmth.

Saint Magnus Cathedral was magnificent in the sunlight with a background of faraway cloud speckling the sky.Nearby, at the war memorial, some men were cleaning the red granite monument in preparation for Sunday’s Remembrance Day service.

All of a sudden a jet plane thundered past. I just managed to pick up the aeroplane in my vision as it disappeared behind the Cathedral’s high roof, flying west. For an instant its size against a tall roof pinnacle looked like some large diving bird.

Well, North Ronaldsay’s harvest home is already behind us.

Great were the preparations: punding for sheep; decoration work; days (and nights) of activity; ‘aaps an doons’ – such as cancellations at the last minute, re-bookings, and so forth.

It was all as good as ever – so everybody says.

But such a day and night as the event took place on! The north easterly wind and rain was a repeat performance of last year’s inclement weather.

Plenty of heating kept the interior of the Memorial Hall comfortable. Among a goodly company of 80 or so were three infants recently born and all having a North Ronaldsay parent.

What a pity the three families were not living in the island. One family does though – Martin and Evelyn who now have a little girl in addition to three boys.

The other two families – Graeme and Gina, living in Stirling, have a boy. And David and Wendy, with their home on the Orkney Mainland, have a daughter.

You know, I often think that if all our Harvest Home visitors, relations, and friends, who come almost every year, were to be resident, how much more satisfying and encouraging island life would be.

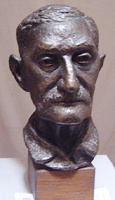

The association’s guest speaker this year was Harvey Johnston, who is a lecturer at the Orkney College.

He is a familiar figure at many Orkney Mainland events as speaker or compere. His wife Helen was also present. Alasdair Henderson, manager of Orkney Ferries was another welcome guest. Our third guest, Rob Crichton (manager of the Orkney Auction Mart) and his wife, Pam, were, unfortunately, unable to attend.

The usual introductions were made which included a short poem written by Howie Firth (who did not manage to come north for the event).

After the supper, Harvey Johnston rose to deliver his Harvest Home address. That took the form of a poem, read, of course, in the Orkney dialect.

This poem, which Harvey was periodically still calmly up-dating during supper, covered North Ronaldsay’s long history from its earliest times up to the present day.

Many of his rhymes caused laughter from time to time. His closing lines advocated, that as well as rounding up the native sheep, we should in fact be rounding up as many peedie bairns as we could.

The toast to the harvest, with ample glasses of the Famous Grouse or sherry glowing in the light of candle and lantern, was then proposed by Harvey and echoed by the company.

Soon the dance got under way with Ann and Lottie Tulloch on accordion, and from time to time Kelvin Scott (specially over from the USA) played his very own fiddle.

Kelvin’s teaching career has changed into that of a professional violin maker.

Sinclair Scott played the pipes for a lively Eightsome reel. Dancing, music and lightsome talk blended grandly throughout the night.

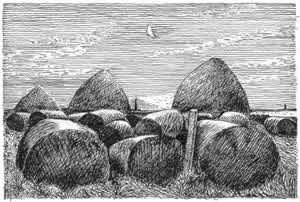

After the dance had been under way for a spell, John Cutt recited a poem, written long before the days of silage and plastic wrapped bales, by his late uncle, William Swanney, Viggie.

After the dance had been under way for a spell, John Cutt recited a poem, written long before the days of silage and plastic wrapped bales, by his late uncle, William Swanney, Viggie.

The title of the poem was, The Hairst O’ Thirty-Eight – actually an account of a particularly bad hairst in 1938 when oats and bere were the main crops.

During a teabreak Ian Deyell conducted a draw for the raffle. Among many kind donations was a generous prize in the form of a painting of a North Ronaldsay sheep’s head by Louise Scott. I myself donated an original painting of the island’s war memorial which was auctioned later by Captain Willie Tulloch.

The total money raised was over £600.

This splendid sum adds to previous successful raffles and includes some very gratifying donations received recently.

Those donations came from a number of members of a diving team (from the south) who explored the wreck of the Swedish East Indiaman, Svecia.

She was wrecked on the nearby reefdyke in 1741.

During a few trips to the island in the 1970s and 80s, when the site was extensively investigated, the divers billeted in the Memorial Hall.

The purpose of our money-raising campaign is to replace windows in this (old, First World War) Memorial Hall.

Next year, some of those same divers plan a nostalgic return visit to the island – a real excuse for a fling and a dance.

Too soon it was time to bring the Harvest Home to a close for another year, and, after one or two more amusing tales told in rhyme by Harvey, the last waltz finally brought the celebrations to an end. Hot soup and sandwiches made the rounds. By about three in the morning most folk had disappeared into the night leaving the old hall dark and silent against a windy, cold Hallowe’en sky. The following day was absolutely beautiful and the cleaning up of the ‘aald hut’ was as enjoyable as ever.

I’ve almost managed this letter in one sitting but I notice, not surprisingly, that it is almost two in the morning. Might as well finish my letter now I think. I had a peep outside, and I see that during the hours I have been writing the moon is now much further west and is seemingly suspended just above Antabreck’s roof. The slates are reflecting its less intense light – for flying cloud continually speeds past the moon. The wind has in fact shifted a little into the southeast and strengthened, and the earlier unrest heard in the sea is more pronounced. Well, it’s good night to the moon, good night to the sea, and goodbye to the old Harvest Home.